Chinese New Year: risk and opportunity

Plus: market sentiment, and more

“No sensible decision can be made any longer without taking into account not only the world as it is, but the world as it will be.” – Isaac Asimov ||

Hi everyone! I hope you’re all doing well. A relatively short email today (you’re welcome!), as I have a schedule squeeze.

🎊 To all readers who celebrate Chinese New Year, I wish you great health, luck and prosperity. 🎊

PUBLISHED IN PARTNERSHIP WITH: ✨ ALLIUM ✨

As traditional finance and crypto converge, trusted data is the missing infrastructure layer. Allium provides this data foundation for teams like Visa, Stripe and Grayscale.

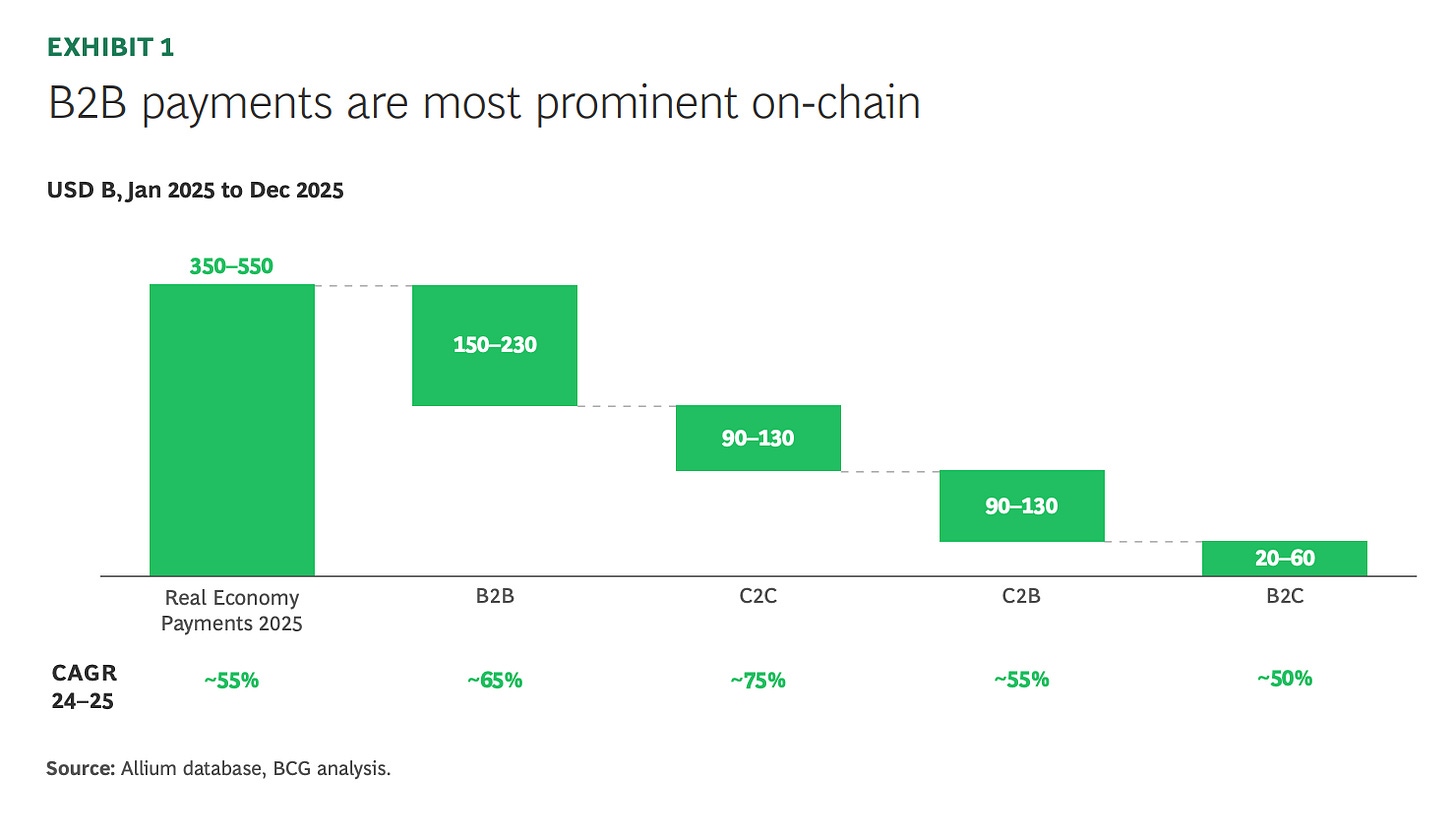

The latest whitepaper published with BCG, Stablecoin Payments: The Truth Behind the Numbers, examines how stablecoins are being used in the real economy today. The analysis estimates $350–550B in on-chain payments in 2025, led by $150–230B in B2B activity, with consumer flows contributing another $200–320B.

If you’re producing institutional crypto research or analytics, start with trusted data. Explore a live demo.

IN THIS NEWSLETTER:

Chinese New Year: risk and opportunity

Markets: still risk-off

Crypto is Macro Now offers ~daily commentary and updates on the overlap between the crypto and macro landscapes. Plus links, a music recommendation (‘cos why not?), and more.

If you’re a premium subscriber, thank you!! ❤

WHAT I’M WATCHING:

Chinese New Year: risk and opportunity

I’ve often wondered why in the West our New Year is in the middle of winter when there is no sign at all of new life. And, so close to Christmas? Couldn’t we spread the festive season out a little bit? The impracticality of the timing becomes even more acute when you realize that it’s largely because of an ancient administrative procedure.

Early Roman calendars began the year in March, near the spring equinox which marked the beginning of both the planting season and military campaigns (March is named for Mars, the god of war).

Then, politics got involved: elections were typically held at the beginning of the year, but this left almost no time to prepare military campaigns. Moving the polls and thus also the start of the year to a couple of months earlier solved that problem. The symbolism also lined up: Janus, for whom January is named, is the Roman god of beginnings, transitions and doorways, with two faces looking both forward and back. Fitting.

Comparing this strategy to that of Asian new year celebrations is illuminating.

The Chinese New Year traditionally marks the beginning of spring planting. It is a time not only for a reminder of the inexorable change of seasons, but also of what have traditionally been considered core cultural values: earth, renewal, family and harmony. Unlike many other millennia-old celebrations, the Chinese New Year has grown in relevance, in part because of the spread of the Chinese diaspora and in part from amplification in global media due to the striking symbols and colours of the festivities.

The economic impact is huge: it’s a trigger for the largest human migration in the world, as millions of Chinese travel to reunite with family and/or to take a vacation. Officially, the holiday extends for just over a week, but many businesses close for a longer period – in aggregate, lost business revenue is often offset by a surge in consumer spending on transport, food, decorations, gifts and leisure.

In China, the occasion is usually referred to as the Spring Festival, to distinguish it from the Gregorian New Year. Around Southeast Asia, countries often have their own local names for the celebration, while those with large Chinese populations tend to use Chinese New Year. A more controversial name for the celebration, increasingly used in the West, is the Lunar New Year.

Chinese sources insist that substituting “Lunar New Year” is disrespectful of the cultural origins, much like wishing Christians “Happy Holidays”. For many, it harks back to colonial Hong Kong when the significance of local celebrations was minimized, to separate the calendar from national identity.

Plus, the celebration technically does not fall on the Lunar New Year. The Chinese calendar follows the lunisolar cycle, which respects 12 lunar months (new moon to new moon) spanning roughly 354 days, but adjusts to prevent seasonal drift by adding an extra month every 2-3 years.

The Islamic Hijri calendar, in contrast, follows the pure lunar cycle, which is why its New Year wanders throughout the months – in 2026, it falls in June.

Now, about the noise and the dancing: according to myth, a ferocious beast emerged on the last day of the year to devour livestock, crops and people. Villagers discovered that the beast hated fire, loud sounds and the colour red, which explains the themes and decorations used to mark the occasion today.

What about the colourful naming? Each year is assigned one of 12 zodiac animals in rotation, which – much like Western horoscopes – is believed to shape the character of those born under its watch. These are combined with five elements in roughly two-year rotations (wood, fire, earth, metal, water), which creates a 60-year cycle. The next ~12 months will be known as the Year of the Fire Horse.

The South China Morning Post has a stunning infographic on the origins of the celebration and its traditions, as well as insight into the Chinese calendar and hours of the day.

It opens with the following text, both ominous and uplifting:

“Folklore historically paints the Year of the Fire Horse, also called the Year of the Red Horse, as one of extreme volatility and unpredictability, leading to fears that it will being danger or social turbulence.

However, traditional Chinese wisdom offers another perspective through the concept of “crisis” (危機).

In this word, the character for “danger” (危) exists alongside the character for “opportunity” (機). This duality reminds us that, even in the most volatile of times, there is always a chance for evolution and growth.

While the Fire Horse – also known as the Red Horse – may bring the heat of rapid change, it also illuminates the path for rapid transformation.”