WEEKLY, Sept 7, 2024

stablecoin philosophy, Argentina's new currency, global governance

Hi everyone, I hope you’re all well! Ugh, true to form, September has been ugly for crypto markets so far. Below I share some September music links that might cheer you up.

Also, I dive into Argentina’s new currency, what Putin’s visit to Mongolia says about global institutions, as well as the conceptual, legal and operational differences between stablecoins and tokenized deposits.

You’re reading the free weekly version of Crypto is Macro Now, where I reshare/update a couple of articles from the past few days.

If you’re not a premium subscriber, I hope you’ll consider becoming one! It’s only $12/month, and you get:

~daily commentaries on the growing overlap between the crypto and macro landscapes,

market narratives,

regulatory moves,

tokenization trends,

adoption news

and more on why this all matters.

I also usually share interesting and often overlooked podcast links, some tangential reads, and music I’m listening to because why not.

Feel free to share this with friends and family, and if you like this newsletter, do please hit the ❤ button at the bottom – I’m told it feeds the almighty algorithm.

In this newsletter:

Stablecoins vs tokenized deposits: the philosophical conundrum

Argentina’s new currency

Putin in Mongolia

Some of the topics discussed the past week:

Nigeria’s crypto strategy

NFTs are securities?

Russia: crypto settlement and bitcoin mining

The ETF Hall of Fame

Thailand’s tokenized handout

Ugh, September

A silver lining?

Argentina’s new currency

Crypto’s quiet quitting

Yield curve rumbles

What next?

JOLTS give a jolt

Swiss banks and crypto

Putin in Mongolia

An intense jobs week

Stablecoins vs tokenized deposits: the philosophical conundrum

Stablecoins vs tokenized deposits: the philosophical conundrum

Tokenized deposits and stablecoins may sound like the same thing, given that they are both fiat-on-chain. But they are actually distinct concepts, and the difference matters for use cases, regulation and our broader appreciation of blockchain potential. They also both highlight, in different ways, how our understanding of money is changing.

Some definitions, please

Tokenized deposits, sometimes known as deposit tokens, are blockchain representations of fiat currency bank deposits. They are issued by banks, backed by fiat deposits at those banks, and can run on either private or public blockchains (although, since these are heavily regulated entities, they’ll want complete control of access). In some cases, such as with JPMorgan’s JPM Coin, they are used to settle transactions between JPMorgan clients. In others, such as SocGen’s EURCV, they can be transferred to clients who do not have accounts at the issuer bank, but only after being whitelisted.

Tokenized deposits boost the efficiency of fiat by eliminating some steps in the execution of trade and settlement, while enhancing transparency and flexibility for their issuers.

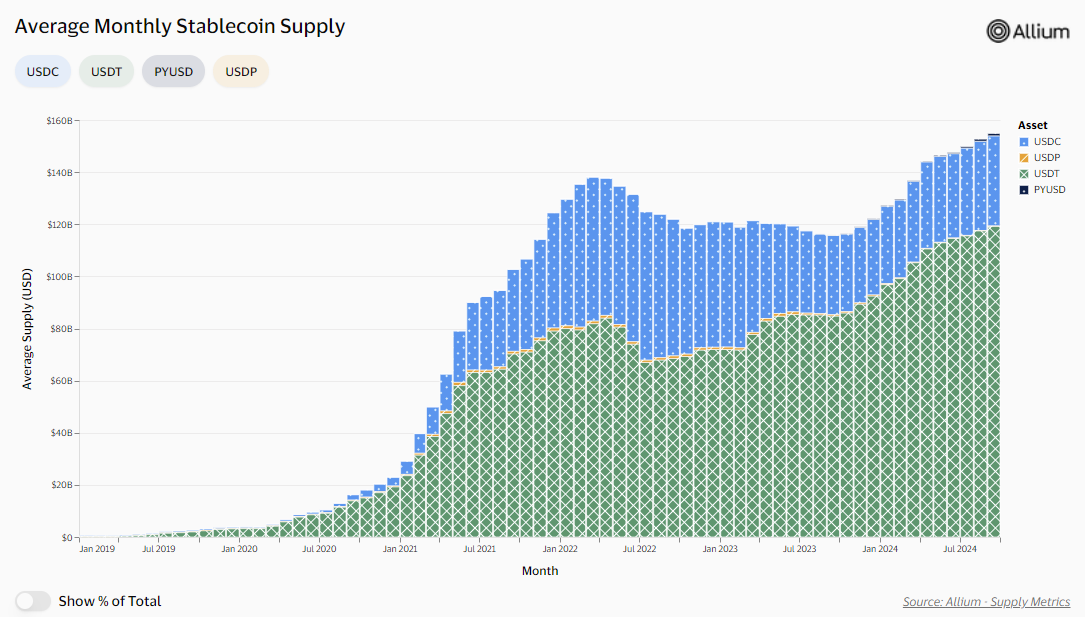

Stablecoins, on the other hand, are blockchain tokens pegged to a fiat currency. The issuer, which may or may not be a bank, promises to maintain the value of the token stable relative to the chosen fiat. Some are algorithmic, with value stability entrusted to a market mechanism – as we have seen, this can spectacularly fail, but some versions (such as DAI) have been working relatively successfully for years.

The most common type is a stablecoin backed by deposited fiat, with redemption for the underlying asset on demand.

(chart via Visa)

This may sound like a tokenized deposit, but it’s not. The stablecoin doesn’t represent the deposit, it is pegged to the fiat value via the deposits: a small distinction that makes a big difference.

The difference is operational, conceptual and legal.

They do different things

On the operational side, the transfer of a deposit token from one client to another usually triggers an off-chain transfer of fiat from one account to another. The tokens represent bank deposits, so the fiat account balances in theory have to match the token account balances. Stablecoins, on the other hand, don’t involve adjusting fiat accounts in the background. They freely change hands between users, and the underlying reserve account doesn’t need to care. It just needs to be available for redemption on demand, it doesn’t matter by whom (this is a slight simplification as not everyone can redeem, but not a significant one – those who don’t redeem can exchange stablecoins for fiat on a number of platforms).

This leads us to the conceptual difference. Deposit tokens are designed to be a more efficient version of traditional deposits, not a substitute. They are not meant to replace fiat money, just make it more efficient.

Stablecoins, however, are more like a substitute. They were originally created as a way to avoid the need for fiat, back in the early days when crypto exchanges couldn’t get bank accounts. They rapidly became not just a workaround but a more efficient way (faster, cheaper) to move funds to and between exchanges, often preferred even when fiat onramps are available.

Deposit tokens are created by banks, for bank clients. They represent bank deposits. Stablecoins were originally created for those who could not get bank accounts. They are a bank deposit substitute. They represent value, not a commercial arrangement.

What’s more, stablecoins are bearer instruments, as in whoever holds them, owns them. They are the asset. Deposit tokens are not bearer instruments. They represent the asset, in this case, named deposits at a bank.

This brings us to the likely legal evolution of the two concepts. In principle, from the regulator’s point of view, bank deposit representations are fine, bank deposit substitutes are more problematic.

Here is where it gets particularly interesting, and where the two concepts unexpectedly start to blend.

Here is also where it gets philosophical.

What does that mean for “money”?

One of the underlying principles of money is its “singleness”, where a dollar is a dollar (to pick one currency), no matter who holds it or how. This is one of the reasons regulators want to control the issuance of dollars, to guarantee that one of the basic assumptions of monetary law will always hold. In a world with multiple dollar issuers and no central guarantor, perhaps not all dollars would be equal.

As we have seen, stablecoins don’t always fulfil “singleness”. One USDT or one USDC (to pick the two largest examples) are not always equivalent to one dollar, although they tend to revert to the pegged value. Therefore, regulators technically cannot consider them “money”. Plus, Tether (issuer of the market’s largest stablecoin USDT) is not insured by the FDIC, therefore the guarantees behind 1 USDT are not the same as those behind $1, which in theory could impact the monetary value (which is not the same as utility).

So, what are stablecoins, then? Securities, along the lines of tradeable money market funds? That would be kind of weird because they are used as money, and they for sure don’t satisfy the Howey prong of “expectation of profit”. “Common enterprise”, another Howey prong, with success tied to a promotor or investor pool, would also be tough to prove.

What’s more, stablecoins fulfil the “establishment” definition of money: they settle transactions, they are widely accepted, they are the unit of account for many assets, they hold their value over time.

But they break the singleness requirement, which is a big deal for regulators who decide who can legally issue and use them.

And if they end up being classified as securities, along the lines of non-yielding money market funds, then we have a melding of previously distinct concepts that could open up a deeper shift in how finance works. Securities, via stablecoins, could become a widely accepted money substitute.

A dollar but not a dollar

Ok, so deposit tokens could be considered money in the eyes of regulators, stablecoins bewilderingly not, right? Not so fast.

Deposit tokens may represent money, but that doesn’t mean they are, legally. For one, they are subject to different types of risk. Bank deposits are not actually all there – most are lent out or invested. So, in the event of a bank collapse, it could turn out that the deposit tokens don’t have the backing everyone thought. The same holds for deposits, but they’re usually at least partially insured. Tokenized deposits, for now, are not.

And a technological glitch could lead to payment misses or even duplication, possibly leading to the deposit token balances not matching the fiat account balances. How would that get resolved?

Furthermore, some innovative bank thinkers talk about the potential to introduce programmability to deposit tokens, enhancing their efficiency and flexibility. Conditional payments are more a wallet question, but it’s not a huge leap to imagine a deposit token that includes a snippet of code that triggers a function, such as access to a bid or payment of a dividend.

This sounds very cool, but it changes the characteristics of the deposit tokens to something more than mere money representation. If a token can become something else, is it still money? Does it satisfy the “singleness” requirement? Does it comply with the establishment definition criteria of medium of exchange, store of value and unit of account?

My hope is that the conundrums presented by the eruption of a new type of transfer technology into the powerful yet limited reach of “old school” monetary economics will open more eyes to the need to update definitions and concepts.

As things stand, regulators are held back by a blinkered adherence to past understanding, refusing to accept that new technologies require new ways of thinking. By limiting “acceptable” uses to things we can already do, authorities are blocking real innovation from helping to both cement and improve on progress.

This brings to mind a quote attributed to Professor Paul Saffo:

“We tend to use a new technology to do an old task more efficiently. We pave the cow paths.”

Surely we can do better, but the first step will be to recognize that the new flying cows no longer need paths, existing definitions of money are unnecessarily limited, and regulators that stand in the way of progress become increasingly irrelevant.

Argentina’s new currency

Bloomberg has a long feature out on an intriguing currency experiment in Argentina. The La Rioja province, no fan of the country’s central government, has issued its own currency, the “chacho” (named after a 19th century local military leader who fought against the government in Buenos Aires – he eventually lost).

It’s a clever scheme: the chachos are not technically currencies, because those can only be issued by the central government – they’re small-denomination bonds that mature in December with a 17% return (~50% annualized), but they can be redeemed at par (1 chacho = 1 peso) before then.

I first wrote about this back in January, wondering what success would look like and what its implications would be. La Rioja is in dire straits because Milei’s austerity administration slashed transfers to the province, where 70% of employees work for the public sector. The local government defaulted on $26 million worth of debt in February, and the same amount again just last week.

If this works, will we see other austerity attempts thwarted by new currencies? In July, when the chacho notes started circulating, Milei’s economic advisor Ramiro Castiñeira insisted that this is fraud, and the “tomb” of government worker salaries. “Wealth can’t be issued.”

(via @rcas1)

Argentina has been down this road before. Back in 2002, several provinces tried this tactic as the supply of dollar-pegged pesos dried up. The peg was soon abandoned, pesos were freely printed and the local alternatives were no longer needed – the results of that monetary policy became tragically apparent years later.

There’s more than a touch of populism here: the notes bear the image of a defiant Ángel Vicente Peñaloza (“Chacho”) carrying an aggressive-looking spear, and a QR code that blasts an anti-Milei message.

(via Numismatic News)

Yet, apart from the colourful imagery, there are bigger questions in play. If the chachos are distributed as part of salaries, spent in stores and gas stations, and used to pay taxes, why aren’t they a currency? Oh, right, only the government can issue currencies.

Another concept worth thinking about is the politicization of currency. In crypto, we’re used to hearing exhortations to “take politics out of money”. What would that even look like, and how would it be enforced? This is especially relevant when blockchain technology makes it relatively easy to spin up digital tokens that can be distributed to certain wallets. If those tokens are fungible and can be used to pay for goods and services, they’re a type of money, right? You can see the outlines of an economic, political and philosophical conundrum ahead.

See also:

Putin in Mongolia

Surprisingly little has been made in the western media about Putin’s visit to Mongolia this week. It’s not so much what happened there that’s interesting – it’s more what didn’t happen. He wasn’t arrested.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) is an independent tribunal established in 2002 to prosecute individuals for international crimes, such as genocide, aggression, war crimes, etc.

In March 2023, the ICC issued an arrest warrant for Russia’s leader, accusing him of the war crime of illegally deporting hundreds of children from Ukraine. Mongolia is one of 123 member states of the international court, which essentially binds it to respecting ICC decisions – a key reason why nations would want to belong is the expectation that the ICC would offer them protection, should the need arise. Notably, Ukraine is not a member. Nor is China. Nor is the US.

Now we wait to see what the ICC does about Mongolia’s defiance. If it does nothing, that could weaken the institution’s clout and undermine the intention of other signatories to abide by its decisions. If the ICC takes action against Mongolia, it’s a public reminder that membership is optional.

The bigger significance would be a fracture, however slight, in the edifice of international governance, where one set of values dictates relationships. Greater global fragmentation is one of the forces behind the renewed increase in gold. This could eventually, once the macro and political uncertainty calms down, start to also show in the levels of interest in its digital peer.

HAVE A GREAT WEEKEND!

True to its reputation, September is turning out to be a pretty dire month for markets so far, especially for crypto. To cheer myself up, I made an incredibly tacky Spotify playlist of September songs, some of the more obvious of which I’ll share with you today. No apologies, if you’re going to wallow, you might as well wallow, right?

Wake Me Up When September Ends, by Green Day.

September, by Sting and Zucchero (yes, really – come for Sting’s voice, stay for the rolling Italian countryside and Zucchero’s velvet jacket).

And then, of course, the ultimate – September, by Earth, Wind & Fire. If this one doesn’t cheer you up, then nothing will (the outfits! the lyrics! the moves!).

DISCLAIMER: I never give trading ideas, and NOTHING I say is investment advice! I hold some BTC, ETH and a tiny amount of some smaller tokens, but they’re all long-term holdings – I don’t trade.